Toronto property assessments are shielded from public scrutiny. This is how we discovered many of us were over-taxed.

We needed just two pieces of information to determine that the mansion on the edge of The Bridle Path neighbourhood was taxed as if it was worth considerably less than its market value.

Its assessed value pegged it at around $4.6 million. But its sale price was millions more.

Finding these pieces of information for this house — and for more than 20,000 other residential properties across Toronto —

was far more complicated. It took nearly two years to collect assessment and sale records to build our own data set to see if homeowners are being asked to pay their fair share of property tax.

In cities across the United States, property assessment and sale data is readily available to the public at large. Elected assessors share it on government websites. It has been used by researchers who have found U.S. assessors, and the methods they use, assign property values that overtax the working class and favour the rich in many cities.

In Ontario, however, that same kind of data is fiercely protected.

The agency in charge of valuating Ontario properties, the Municipal Property Assessment Corporation (MPAC), has a long history of successfully arguing that property owners should be denied their requests to see larger volumes of assessment data and details of its calculations on the grounds that releasing such information would harm its economic interests. The corporation, which is funded almost entirely by taxpayers, has been compared to “the Kremlin” by one Toronto city councillor.

MPAC says its work is accurate, fair and easy for the public to access. It says the information it provides online allows homeowners to understand and challenge their assessments.

“We’re more mature, more transparent and we’re far more accountable than we used to be,” said Carmelo Lipsi, vice- president and chief operating officer.

In April 2021, we asked MPAC for its assessment and market- value data for all residential properties in Ontario.

We wondered if the corporation might be eager to pull back the curtain to show how far it’s come since 2006 when Andre Marin, Ontario’s ombudsman at the time, described MPAC’s valuations as “sophisticated guess work” and noted the “wide margins of error” the industry allows assessors.

The agency told us the data wasn’t entirely theirs to give. While sales data belongs to the province, it is licensed to a company called Teranet, which has an exclusive contract to operate Ontario’s electronic land registry. MPAC relies on this sales data to develop property values and said it would need Teranet’s permission to provide the Star with its assessment records.

We met with MPAC and Teranet representatives. We explained that disclosure of sales and assessment data was in the public interest. Teranet wanted to know what we planned to report before handing anything over. Until we saw the data, we said, it was impossible for us to speculate on what any story might say. Teranet denied our request.

So we found the data ourselves.

To see how closely MPAC’s assessed values were to market values, we focused on collecting data on Toronto houses that sold in 2016, the last year MPAC conducted a provincewide assessment update of property values.

Ontario’s Assessment Act says assessments must reflect a property’s “current value” as of a specific date set by the provincial government. In Ontario, the current assessment cycle is pegged to Jan. 1, 2016, meaning MPAC’s property assessments should represent prices that unrelated buyers and sellers would agree to as of this date.

We sifted through property records to obtain 2016 sales for tens of thousands of residential properties. Finding the assessment value for each of those was trickier.

City prohibited from sharing assessment list

Toronto Coun. Mike Colle says he’s dealt with the Municipal Property Assessment Corporation (MPAC) throughout his political career. “I’ve always called it the Kremlin.”

Andrew Francis Wallace

The Assessment Act requires MPAC to provide all municipalities with an annual assessment roll that lists all properties within their jurisdiction by address along with owner names, assessed values and legal descriptions of the properties.

We asked the City of Toronto for a copy of its digital roll. We were told its licensing agreement with MPAC “expressly prohibits” such data sharing.

“I’ve always called it the Kremlin,” Toronto councillor Mike Colle said of MPAC.

Colle says he’s dealt with the agency throughout his political career, as an Ontario Liberal MPP and most recently as the municipal representative for Eglinton-Lawrence where he’s helped constituents challenge their assessments.

“It really is not people friendly and it’s not willing to share information that makes sense to ordinary people,” Colle said. “Nobody is really holding them to account in any way, shape or form.”

The Star used publicly accessible computer terminals at Toronto City Hall that allow residents to look up assessment records, but only one address at a time. Over the course of a year, we built a data set of roughly 20,000 residential properties.

We shared our data with University of Chicago professor Christopher Berry and Illinois-based data scientist Eric Langowski, who have extensively studied the U.S. assessment industry. They analyzed our data set using the same methods they used when studying assessments in thousands of U.S. jurisdictions, including Chicago, New York and Detroit.

We shared our findings and even our raw data with MPAC.

Thousands of properties excluded

The agency said thousands of properties in our database, many of them recently constructed condos, could not be included in a fair analysis. MPAC said when purchasers buy condo units directly from the developer — a common way new homeowners get into the market — such transactions cannot be considered “arm’s length,” meaning they don’t represent deals between knowledgeable, willing buyers and sellers.

MPAC also excluded thousands of additional properties where it said our records did not precisely match theirs; if, for example, the sale date differed.

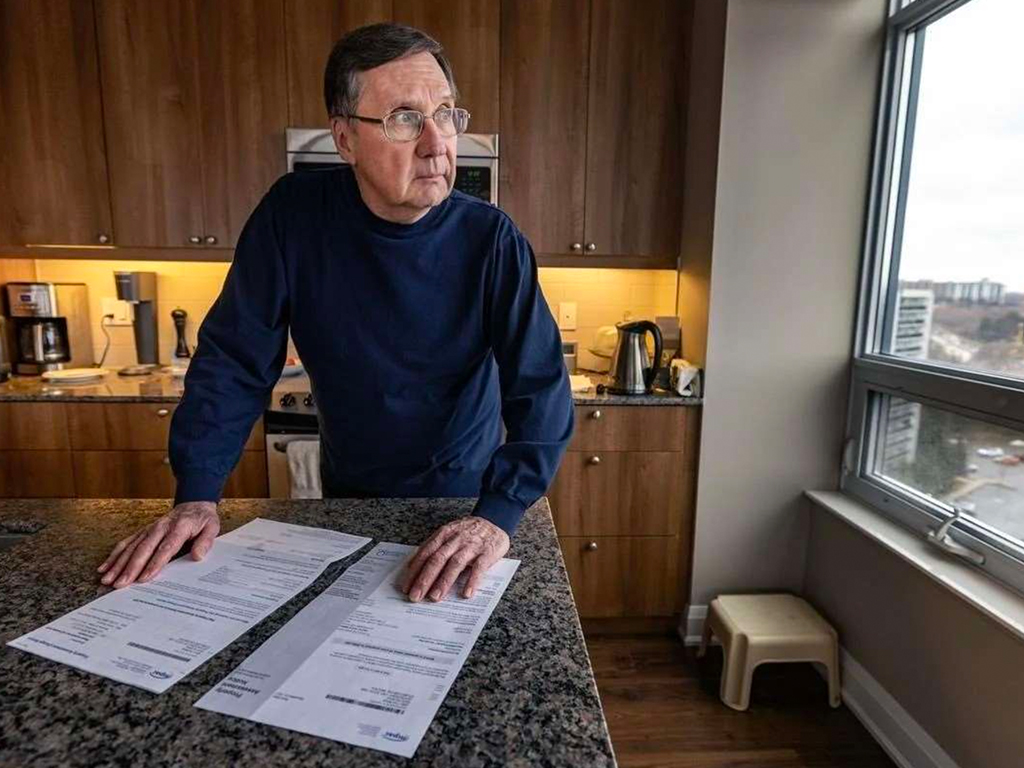

Thomas Sinyi’s condo is among the properties MPAC said we could not use in our analysis. The retiree downsized into a newly built Etobicoke tower in 2016. He doesn’t understand why MPAC assessed his 1,200-square-foot, two-bedroom suite at $590,000 — about $100,000 more than he and his wife paid.

“I feel I’ve been cheated,” said Sinyi, 70.

In one assessment notice he received, Sinyi learned that as of Jan. 1, 2012, shortly after he agreed to purchase the unit, MPAC had assessed his yet-to-be-built unit at $531,000. At the time, there was nothing but a sales office on the lot, he says.

MPAC said it would not comment on individual homeowners’ assessments. But the agency said assessments must reflect market values as of a specific legislated date, not necessarily the price a buyer and seller agreed to several years prior to occupancy as is typically the case for newly built condos.

In the end, MPAC eliminated some 8,600 properties from our sample. About 60 per cent of these were among the cheapest homes bought in Toronto that year — the type of property researchers have found are disproportionately over-assessed relative to others.

That left us with about 11,800 properties that MPAC considered “valid” for analysis. MPAC “time-adjusted” the sale prices of these houses to reflect the market on Jan. 1, 2016. We used the agency’s adjusted prices in our analysis.

Star investigation found troubling inequity

Christopher Berry, a University of Chicago professor, has been studying the assessment industry for nearly a decade.

If a home was assessed at an amount within five per cent of its sale price, then the Star counted it as an accurate assessment. Anything outside of that range we considered over- or under- assessed.

We found troubling inequity.

The cheapest 10 per cent of homes in the Star’s data sample sold in 2016 for about $328,000 or less. Of those, 31 per cent were assessed at more than what they sold for. Roughly 20 per cent were under-assessed.

Only 21 per cent of the most-expensive homes, which sold for between $1.6 million and $14.7 million, were over-assessed while 42 per cent were under-assessed.

MPAC says it disagrees with the Star’s findings. “We have concerns about how the data was obtained and about the methodology,” a spokesperson said.

The agency said it recorded some 38,000 residential property sales in 2016 that were valid for analysis — more than three times the size of the Star’s data set. MPAC said its analysis of those records found its assessors’ work met international standards and was fair to Torontonians.

MPAC’s data set, we learned, includes some condo lockers and parking spaces as residential property sales.

An offer, with strings attached

After sharing our initial findings with MPAC last November, the agency offered to provide us with Toronto residential assessment data. The offer required the Star to name sources with whom we might share the data and allow MPAC to order an inspection of the Star’s records and offices for the next two years.

MPAC also required the Star to agree to not focus on individual properties but report exclusively on broader trends.

This restriction meant we could not tell readers about a rowhouse in Malvern that we found was taxed as if it was worth

$55,000 more than it sold for. Or the detached brick two-storey in exclusive Hoggs Hollow, with four fireplaces, a nanny suite and an assessment that meant it was taxed as if it was worth much less than its $3.95-million price tag.

Had we signed the contract, another stipulation would have prevented us from even reporting the existence of the contract.

We refused to sign the agreement.

MPAC said these “standard terms and conditions” could not be waived without Teranet’s approval. MPAC told us Teranet would not waive these conditions.

Teranet told the Star its contract with the province prohibited it from providing bulk address-level data without permission. We contacted the Ministry of Public and Business Service Delivery, the ministry Teranet told us it deals with. Despite numerous calls and emails to the minister’s office and his staff, we never heard back.

‘Need for transparency’

“There’s a need for transparency and assurance that the people of this province are getting a fair assessment at a fair cost,” said Lewis Auerbach, a former director in the federal auditor general’s office.

Auerbach collided with MPAC’s secrecy in 2001 when he was working on a City of Ottawa task force looking into property taxes and the assessment system.

Ontarians, he said, should be concerned with MPAC’s “enormous” lack of transparency and accountability.

The Toronto Star is excited to share with the public the results of our team’s work these past two years. We hope our readers learn from this series and ask questions. Please share with us your experiences, your questions and concerns about the assessment system we all pay for.

Thomas Sinyi fears the new Etobicoke condo he moved into in 2016 has been over-assessed by $100,000. Andrew Francis Wallace / Toronto Star

Leave A Comment